GE’s Ecomagination initiative, launched May 9, 2005, certainly turned heads. Here was the world’s ninth-largest company, a 113-year-old conglomerate founded by Thomas Edison, inventor of the first commercial light bulb, putting sustainability front and center of its new corporate strategy.

It seems, 20 years later, paradoxically overhyped and underappreciated.

At first glance it appeared to be a slick marketing campaign, complete with fun TV commercials (such as this one, aired during the 2011 Super Bowl, featuring an electric cow). But Ecomagination turned out to be much more than that.

On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Ecomagination’s debut, I’ve been reflecting on GE’s bold initiative and its implications for today’s companies. What did Ecomagination teach us about heavily marketed sustainability strategies? What impact did it have on GE’s business and reputation? How would an Ecomagination-like initiative fare in today’s complex business and political environment?

And what are the lessons learned from the entire effort?

What was Ecomagination?

When GE’s then-CEO Jeff Immelt took the stage at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. to announce Ecomagination, the company was seen as a laggard in sustainability, if not an outright eco-villain.

The company — which at the time manufactured everything from lightbulbs to aircraft engines to large healthcare devices such as those used for MRI and CAT scans — had a long and unenviable environmental reputation. Over a 30-year period starting in the mid-1940s, GE released more than a million pounds of toxic PCBs into the upper Hudson River, a byproduct of its nearby manufacturing of electrical capacitors. Over time, PCBs contaminated nearly 200 miles of the Hudson, making it the nation’s largest Superfund site. (In 2015, GE announced that it had removed the majority of the toxins, at a cost of more than $1 billion.)

At the same time, GE’s business customers were seeking to reduce their energy spend along with their greenhouse gas emissions. Immelt and his team saw a significant business opportunity that might also dig the company out of its reputational hole.

So GE committed to:

- Double its annual revenue from “clean technology” products, from $10 billion in 2005 to at least $20 billion by 2010, “with more aggressive targets thereafter”

- More than double its research investment in cleaner technologies, from $700 million in 2004 to $1.5 billion in 2010

- Reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 1 percent by 2012 and the intensity of its greenhouse gas emissions 30 percent by 2008, both compared to 2004. (Based on the company’s projected growth, GE said its emissions would otherwise have otherwise risen 40 percent by 2012)

Given the company’s environmental history, GE’s announcement was met with skepticism. Critics called it “greenwashing,” among other epithets, noting that the company continued to operate in polluting sectors such as coal and oil. Moreover, Ecomagination included technologies that would make oil sands production and natural gas fracking marginally cleaner, which sustainability experts and activists saw as fundamentally misaligned with true climate leadership.

But GE was also ramping up production of wind turbines, solar inverters, electrified locomotives and a dozen or so other truly cleaner technologies.

What went right?

The company made clear that Ecomagination was unabashedly about growing revenue. Its goal was to drive business growth through clean technology, energy efficiency and environmental stewardship, while also improving GE’s own operational footprint.

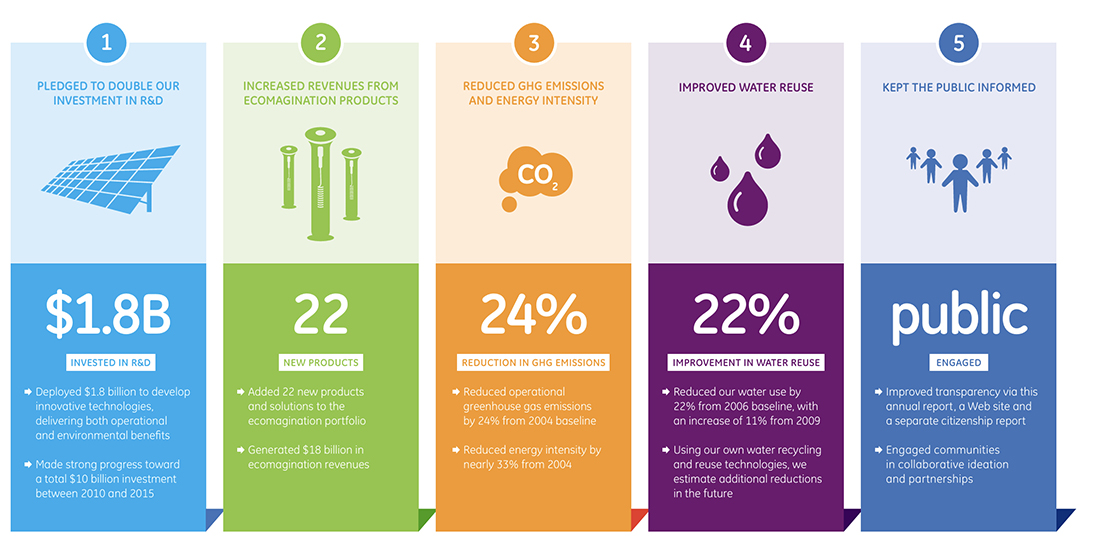

In that regard, the company exceeded its goals. By 2010, five years after launch, GE claimed $85 billion in cumulative Ecomagination revenue. (The company used a third party to assess and certify whether products and associated revenue met the Ecomagination standard.) It also could boast impressive gains in reduced emissions, water use and other metrics.

Ecomagination’s 5-year status report

One key success factor was that Ecomagination goals were owned by the entire company leadership. “This was GE board-level approval. The biggest champion was the chairman and the CEO,” Deb Frodl, the company’s chief marketing officer at the time and later head of Ecomagination, told me recently.

And money talked. The fact that GE could show impressive revenue growth from its greener products from the get-go gave the program solid momentum, internally as well as externally.

Moreover, it won over some critics, including Mindy Lubber, CEO of Ceres who, in a previous role, led the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in the Northeast region, including overseeing litigation related to the Hudson River cleanup. Lubber was one of GE’s eight-member Ecomagination Advisory Board.

“For the CEO of one of the largest multinational companies to sit through four-hour meetings and six-hour meetings and followups to make sure your input was heard and their goals were clear, I think that stayed pretty consistent,” Lubber told me.

What could have gone better?

Policy support, for one. “We thought federal policy and smart regulation would follow, and that didn’t happen,” said Frodl. “Cap-and-trade didn’t happen. The Clean Power Plan didn’t happen. There was just nothing to give us the tailwinds.”

There was also a messaging muddle. The initiative’s broad scope — encompassing both breakthrough technologies and incremental efficiency improvements — blurred the line between what was truly game-changing and what was business-as-usual. And the company’s unwillingness to divest from its “dirty tech” businesses or prioritize emissions reductions beyond legal requirements fueled skepticism about the depth of its environmental commitment.

What was the outcome?

By the time Ecomagination was shuttered in 2017, it had achieved significant results in business growth, R&D investment, emissions reductions and other key metrics. According to Frodl, writing in 2017, during Ecomagination’s 12-year life, GE

- Invested $20 billion in Ecomagination solutions

- Generated $270 billion in revenue

- Reduced greenhouse gas emissions and freshwater that saved the company more than $480 million

- Saved GE customers more than $3 billion in energy and water costs while helping them reduce more than 5 gigatons of greenhouse gases

But even those stats belie the greater changes in GE, said Frodl. “I honestly believe that it changed the company for the good. It culturally changed the mindset to be ‘We’re innovating some of the world’s most efficient technologies.’”

Could Ecomagination exist today?

It would be difficult, particularly in the United States, where political forces are keeping corporate sustainability initiatives low-key, and in Europe, where aggressive greenwashing rules would likely tamp down some of the bold commitments GE made in 2005.

That doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen, said Lubber. “It should happen with most large businesses. Informed, stakeholder input that’s done in the right way, where it’s not about throwing bombs on street corners, but it’s about hearing each other is a helpful thing.”

What were the learnings from Ecomagination?

Business first, sustainability second: Ecomagination was explicitly a growth strategy, not an environmental mission. GE’s leadership was upfront that the initiative’s goal was to drive business value by capitalizing on emerging demand for cleaner technologies.

Rebranding vs. reinvention: Much of the early success came from rebranding existing products (such as wind turbines and efficient turbines) as Ecomagination products rather than fundamentally transforming GE’s business or divesting from polluting sectors. This approach raised questions about the depth of the company’s commitment to sustainability.

Scale and impact discrepancy: While Ecomagination generated billions in revenue and notable environmental progress, these achievements were modest relative to GE’s overall scale. For example, its Ecomagination Challenge, an open-innovation process that solicited ideas from individuals and start-ups to identify potential energy ventures for GE to invest in, led to $140 million of investments, a mere blip when considering GE’s $37 billion energy business.

Skepticism and legacy issues: Despite public commitments and transparent reporting, GE continued to face scrutiny from environmental groups — especially around legacy pollution issues, such as the Hudson River cleanup. The company’s marketing prowess sometimes outpaced its substantive change.

Innovation and collaboration, within limits: Ecomagination’s open innovation efforts fostered collaboration and generated thousands of ideas. But the scale and timeline for these innovations to materially affect GE’s core business highlighted the challenge of integrating breakthrough sustainability into large, established firms.

The cautionary tale of Ecomagination is that even well-publicized, well-funded and board-backed corporate sustainability initiatives can fall short of transformative change if they prioritize business growth over systemic environmental impact, rely heavily on rebranding and fail to fully address legacy issues.