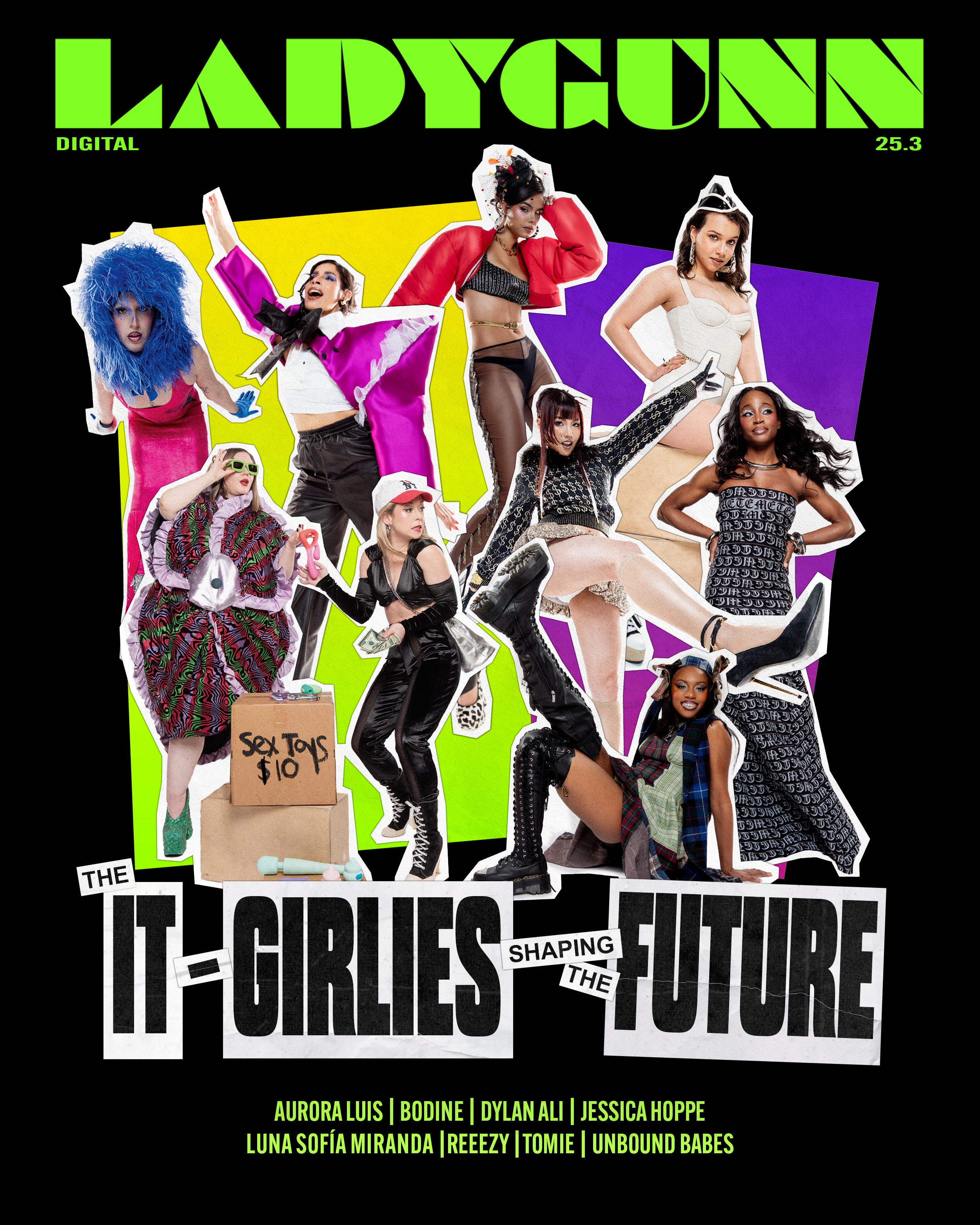

Feature Editor / Koko Ntuen

Photos / Felipe Zapata-Valencia

CD + Styling / Phil Gomez

Beauty Editor / Rory Alavrez

Cover Art / Mikey Meza-Pérez

Hair Stylist / Isaac Davidson / Che Nieves

Styling Assistant / Alon Cameron

MUA / Anaiyah Simmons / Nyala chamberlain / Sophie Hartnett

Jessica Hoppe is an unapologetic storyteller, a cultural critic, and true NuevaYorka, a platform that pulses with the energy of Latinx identity, heritage, and the magic of New York City. A Honduran-Ecuadorian writer with bylines in The New York Times, Vogue, and beyond, Hoppe has built a career on radical honesty—unpacking mental health, addiction, and the first-generation experience with the kind of vulnerability that shifts narratives.

Her debut memoir, First in the Family, is a heart-wrenching and powerful account of addiction, recovery, and the pursuit of the so-called American Dream—earning its spot on 2024’s Best Memoirs lists in Esquire, People, San Francisco Chronicle, Marie Claire, and HipLatina. But beyond the accolades, Jessica’s work is a beacon for those navigating identity, healing, and the complexities of belonging.

As a board member of Time of Butterflies, a nonprofit supporting survivors of domestic abuse, and an organizer within the Central American Writers’ Group, Jessica isn’t just telling stories—she’s amplifying voices that have long been silenced. Through NuevaYorka and her writing, she continues to redefine what it means to be an It-Girl and a Latina in media today—on her own terms, with her own words.

Was there a moment when you realized the power of your words, and how did that shape your voice?

Before we begin, can I just say giving an interview on the first day of Mercury Retrograde feels like a dare and I would always go with Truth the times I played [Truth or Dare] and just lie. I’m in recovery (from substance use disorder) now, so I can’t lie, but I’m going to proceed with caution (haha). Please bear this in mind, dear reader.

Speaking of rigorous honesty, as we say in recovery, I’d love to give you a polished answer. But the truth is I’m still learning the power of my voice, even at 42 years old, even as a published author.

The moments I’ve spoken up were often forced. You know that righteous anger? The irrepressible human spirit and dignity resounding in the face of power—forces far more powerful than me. But when I spoke up despite my fear, I always met someone who said, “Thank you,” or “You said what I was thinking,” or “I’m not going to stay silent next time.” And that is so important because it proves we’re not alone. And that makes us all safer, stronger.

Jacket, Megan O’ Cain. Shirt, Lindsey Media.

How do you navigate the nuances of identity, both personally and within your work?

It’s funny (and by funny, I mean tragic, of course) because we’re living through a time now where terms like diversity, equity, and inclusion have become a dog whistle—used to incite hatred, erased from history books, websites, corporations, and universities. I was just updating my bio, and in the very first sentence, I identify as a Honduran Ecuadorian writer. I considered changing it, not for fear but because I didn’t see most writers identifying by their ethnic background, and why should they? Even if you are part of a group that is disproportionately underrepresented in your industry, you, yourself, are not the spokesperson for those people, right? So you have to decide if it’s important to you and why. For me, it’s my mother and my father. It’s because, through the process of forced assimilation, we were taught to be ashamed of where we come from. Every aspect of my identity is influenced by a place I’ve never physically been, a place where people have fought against colonialism and imperialism and survived, a place I yearn for that makes me who I am. And I am so proud of that. I’ll never let anyone take the truth of my history and my people from me again.

Who are the women that have shaped your journey, and how do you hope to inspire the next generation?

Though she never used the term in her life, my mother was the one who taught me how to advocate for myself and others. My sisters, fierce and outspoken, were who I looked up to. Still do. Of course, there were public figures, writers like Toni Morrison, who altered my thinking—and convinced me this outrageous dream was important, perhaps even attainable.

My sister just texted me a page from Toni Morrison’s book, The Source of Self-Regard, which is like a bible between us. The final paragraph says:

I am a writer and my faith in the world of art is intense but not irrational or naïve. Art invites us to take the journey beyond price, beyond costs into bearing witness to the world as it is and as it should be. Art invites us to know beauty and to solicit it from even the most tragic of circumstances. Art reminds us that we belong here. And if we serve, we last. My faith in art rivals my admiration for any other discourse. Its conversation with the public and among its various genres is critical to the understanding of what it means to care deeply and to be human completely. I believe.

What does being an It-Girl mean to you?

Ummm, that I have fabulous friends who see me in a way I strive to see myself 😉

That I used to be a party girl…

No, for real, I think an It-Girl means you’ve been seen, right? Someone, some org, institution, or entity, sees something in you that they deem worth looking at and listening to. So, I’m most interested in the arbiters because knowing their values will tell everything you need to know about the message they want to send. For so long, those have been (and continue to be) noxious: eurocentric beauty standards, heteronormativity, obsession with wealth, whiteness, and elitism. The list is endless! I think LadyGunn does a great job at disrupting the norm by interrogating those. Which is how I got here, right…because I’m not rich, white, or elite hahaha. Just so we’re clear.

What’s something about Jessica Hoppe that people might not know but should?

My hype music is the Ugly Dolls soundtrack. Among various Cardi B, Doechii, Princess Nokia tracks. I can’t make a playlist to save my life. Also, something embarrassing I probably don’t want anyone to know but fuck it.

Also, whatever you see me out here screaming about or protesting is something that I am contending with myself. I don’t have the answers. I acknowledge the ways that I, too, am complicit. I’m constantly wondering if or how admitting our complicity can empower us to dismantle and redefine dominant narratives. Perhaps that integral step is what can help us begin to create a safe space.

If you could send a love letter to your future self, what would it say?

Everything we’re taught to be ashamed of is nothing to be ashamed of! Shame took (still takes) years of our precious time, creativity, and peace of mind. When it comes up for you—when it tells you to shut up, hide, or that you’re wrong or stupid—pause. Question what shame tells you. Don’t allow it to lie to you or control you. Know the truth, then let it guide you.

What message do you hope to send to young girls who see you owning your space as a writer?

I published my first book six months ago, weeks before my 42nd birthday. Publishing is my fourth official career, my 4000th unofficial career; I’ve had every job known to man, but writing has always been what I wanted to do more than anything. I was busy surviving for a long time, and that’s OK. You might be giving up hope. The world is indeed on fire. But this is when we need you most—the dreamers, artists, fighters, organizers. Let it rip! Don’t give up. Fuck timelines and goalposts and what anyone thinks. Exceptionalism is a trick. There’s no clear path or right way. We can only choose our next right action based on what we see in front of us. What rings true in our hearts. One step leads to the next until, miraculously, a clearing appears. What changes most of all, and, most importantly, is you.

Luckily, those are the most interesting things to write about.

What’s next for you, any new stories or chapters in the works?

While researching my first book, First in the Family, I talked with my uncle about desire—what he negatively observed about my grandmother, which I saw as an inspiring example. As a person in recovery who’s chosen abstinence, I’m often considering how the extremities of desire interact with sobriety—how they frequently act as co-conspirators in how we treat people. The language of abstinence—of being “clean,” deprivation, and controlling one’s desires—informs the subtext of our narratives and upholds the systems of oppression that create addiction in the first place. In turn, repression is confused with resistance. These are the subtexts of white supremacy and its all-encompassing and inescapable logic. This is the thesis of my next book. I want to examine love and relationships the way First in the Family interrogates recovery. If FitF asks who is entitled to heal, my next book asks who is entitled to love?

Full look, DELOSANTOS. Shoes, BAPE.