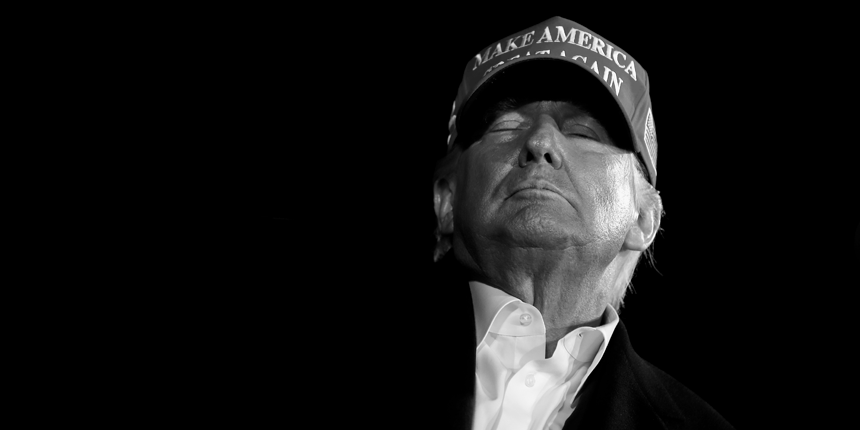

The “Make America Great Again”, or MAGA, as it is more commonly known, has profoundly shaped American economic policy through its advocacy of an “America First” approach.

Over the remainder of this decade, it will inevitably continue.

This economic model prioritises protectionism, tariffs, deregulation, tax reform, domestic energy production, and the renegotiation of trade agreements to bolster American industries and workers.

While designed to revitalise the United States economy, this inward-looking strategy carries significant implications for America’s trading partners, potentially reshaping global trade dynamics.

This Grey Data blog entry is effectively a brief analysis of the economics of MAGA. It explores the key components of MAGA economics model and evaluates how these policies are likely to affect countries that engage in trade with the United States, considering both immediate impacts and broader, long-term consequences.

Key components of MAGA economics

Tariffs and protectionism

A cornerstone of MAGA economics is the imposition of tariffs on imported goods to shield American industries from foreign competition. This protectionist stance aims to make domestic products more competitive, thereby boosting employment and growth in sectors such as manufacturing, steel, and agriculture.

During Donald J Trump’s first term as POTUS, tariffs were levied on imports from major trading partners, including Canada, China, and the European Union, with indications that similar measures could expand under future MAGA-aligned policies.

The intent is clear: reduce reliance on foreign goods and encourage the resurgence of American production.

Deregulation and tax reforms

The MAGA model also emphasises deregulation and tax reform to stimulate business growth.

By reducing regulatory burdens, such as environmental or labour standards, and lowering corporate tax rates, the approach seeks to create a more attractive environment for investment and entrepreneurship in the US.

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, a hallmark of Trump’s economic agenda, exemplifies this strategy, slashing corporate taxes to spur domestic economic activity. These policies aim to repatriate capital and jobs to the US, enhancing its economic competitiveness.

Domestic energy production

Energy independence is another pillar of MAGA economics, with a focus on expanding domestic oil, gas, and renewable energy production.

By reducing reliance on imported energy, the United States seeks to strengthen its economic sovereignty and insulate itself from global energy market fluctuations. This shift has been supported by policies promoting drilling, fracking, and infrastructure development, aiming to position the US as a net energy exporter.

Renegotiating trade agreements

The MAGA movement advocates for revisiting international trade agreements to prioritise American interests. A prominent example is the replacement of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which introduced provisions to favour American workers and manufacturers, such as stricter rules of origin for automobiles.

This renegotiation reflects a broader intent to recalibrate trade relationships, ensuring they align with the “America First” ethos.

Impacts on key trading partners

The MAGA economic model, while focused on domestic gains, sends ripples across the global economy, affecting trading partners in diverse ways.

Below, we examine how each component influences countries that rely on trade with the United States.

Tariffs: economic strain, pain, and trade diversion

Tariffs imposed on imports from countries like Canada, China, and the EU directly increase the cost of their goods in the US home market, potentially reducing export volumes.

For Canada and Mexico, who were/are key partners, this could translate to severe economic strain, particularly in industries like automotive manufacturing, metals, and agriculture, which depend heavily on access to the American market.

China, which is a major exporter of electronics and consumer goods, might also see its trade surplus with the US shrink as tariffs bite, though its ability to pivot to other markets could soften the blow.

However, the impact is not uniformly negative. Some economists suggest that tariffs could lead to trade diversion, where reduced imports from targeted countries create opportunities for others. As an example, if Canadian or Chinese goods become less competitive, emerging nations like Vietnam or the potential future superpower India might step in to supply the US, gaining market share.

Within the European Union, certain companies could benefit if trade flows shift away from heavily tariffed partners. However, President Trump seems to have his goals set firmly on winning manufacturing business from the large Eurozone economy, with Germany and the Benelux nations especially likely to be hit hardest.

Nonetheless, the overarching effect of tariffs is likely to disrupt established supply chains, compelling trading partners to adapt swiftly or face economic losses.

Tariffs carry the risk of retaliation

Canada, China, and the EU have previously threatened and responded to US tariffs with counter-measures, targeting American exports like agriculture and machinery.

Such tit-for-tat actions could escalate into trade wars, raising costs for consumers and businesses worldwide while dampening global economic growth.

Deregulation and tax reform

The US’s deregulatory and tax-cutting measures could shift global investment patterns, drawing capital away from trading partners with stricter regulations or higher taxes.

Multinational corporations might prioritise the US as a base for operations, potentially reducing investment in countries like Germany or Japan, where regulatory frameworks remain more stringent. This could lead to job losses and slower growth in those economies, particularly if they struggle to match America’s business-friendly policies.

Alternatively, trading partners might respond by adopting similar reforms to stay competitive. However, this all risks sparking what is known as “the race to the bottom,” where nations sacrifice tax revenues and (perhaps more controversially) regulatory standards, such as environmental protections in order to attract investment.

For developing countries with less fiscal flexibility, competing with a deregulated US could prove challenging, widening economic disparities.

Domestic energy production: shifting energy markets

The push for energy independence could significantly affect energy-exporting nations. Canada, a major supplier of US oil, might see reduced demand as American production ramps up, impacting its energy sector and broader economy.

Similarly, OPEC countries like Saudi Arabia could face declining American imports, forcing them to seek alternative markets or diversify their economies—a difficult transition for oil-dependent states.

On the flip side, reduced US demand might lower global energy prices, benefiting energy-importing nations like Japan or India.

Trading partners with emerging renewable energy sectors could also find opportunities if the US outsources specific technologies or components. Nevertheless, the shift toward US self-sufficiency is poised to reshape global energy trade, requiring exporters to recalibrate their strategies.

Renegotiated trade agreements

The MAGA focus on rewriting trade deals to favour the US could strain relations with partners like Canada and Mexico. Under the USMCA, for instance, higher labour and origin requirements might increase production costs for these countries, reducing their competitiveness.

If other agreements, such as those with the EU or Japan, are similarly revised, trading partners may perceive the US as an unreliable negotiator, prompting them to deepen ties elsewhere, such as through the EU-Mercosur pact or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

This approach risks isolating the US from new trade opportunities, as partners grow wary of one-sided terms.

Over time, it could diminish American influence in global trade forums, pushing allies toward alternative economic blocs.

Broader implications: trade wars and global fragmentation

The MAGA model’s protectionist bent heightens the risk of trade wars, as seen in the US-China tariff clashes of 2018-2019.

Retaliatory measures could spiral, disrupting supply chains and raising costs across borders.

Historical data suggests that such conflicts reduce global GDP, with developing economies often bearing the brunt due to their reliance on export-led growth.

More fundamentally, MAGA economics challenges the post-World War II paradigm of globalisation and free trade.

By prioritising national interests over multilateral cooperation, the US might encourage other nations to adopt protectionist policies, leading to a fragmented global economy.

This could undermine the efficiencies of comparative advantage, slow innovation through reduced competition, and weaken international institutions like the World Trade Organisation.

MAGA economics and the MAGA economic model, which is being built on tariffs, deregulation, energy independence, and trade renegotiation, seeks to fortify the US economy by placing American interests first. Yet, its impact on trading partners is multifaceted.

While some nations may face export declines, investment losses, or strained relations, others could gain from trade diversion or market shifts.

However, the model’s broader consequences, potential trade wars, competitive deregulation, and a retreat from globalisation, suggest a high cost for global economic stability.

As the US pursues this path, its trading partners must navigate a complex landscape of risks and opportunities, adapting to a world where protectionism increasingly defines the rules of engagement.

At this time, it is worth summarising my thoughts. The long-term success of MAGA economics will depend not only on its domestic outcomes but also on how the global community responds to this seismic shift in trade dynamics.

The massive international impact of Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) seems to point to the economics and policy decisions being more likely to catch on globally.

MAGA economics could well be here to stay.