As one previous post on this blog detailed, the current political turmoil in Northern Ireland was sparked by a subsidy for renewable energy production. Though it is tempting to blame political carelessness, the ongoing RHI scandal prompts a broader reflection about renewable energy policy instruments. Incentives akin to the RHI are relatively common in renewable energy policies across Europe and it is not the first time that they create difficulties. From the abrupt halt to support to photovoltaics in Spain in 2009 to issues with the territorial planning of incentivised wind power in France and Germany (or near Donald Trump’s golf course…) renewable energy policy can prove hard to manage, even (or especially?) when it relies on apparently simple market-based instruments.

Looking back on the French photovoltaic crisis

The history of solar photovoltaics in France is a good illustration, as I retrace in a recent paper in Environmental Politics. The uptake of photovoltaics in France was driven by a feed-in tariff scheme set up in 2006. These feed-in tariffs offered a fixed payment over 20 years for each unit of electricity generated by photovoltaic appliances and fed to the grid. Their introduction in France was directly inspired by the German FIT-based renewable energy policy. However, while the 2006 feed-in tariff scheme imported its basic template from Germany, it did not copy the features designed to control implementation and uptake. For example, tariffs were not set to decrease every year to follow cost evolutions, as they do in Germany. In addition, the policy did not create institutional or political arrangements to monitor implementation, and very limited manpower was devoted to its management within ministries. Photovoltaics, one of the least mature renewable energy sources, was clearly not intended to contribute significantly to a French electricity mix dominated by nuclear power; the incentive was expected to have only marginal effects, as is explicitly stated in the document planning investment in the electricity sector for 2005-2015 (p. 48).

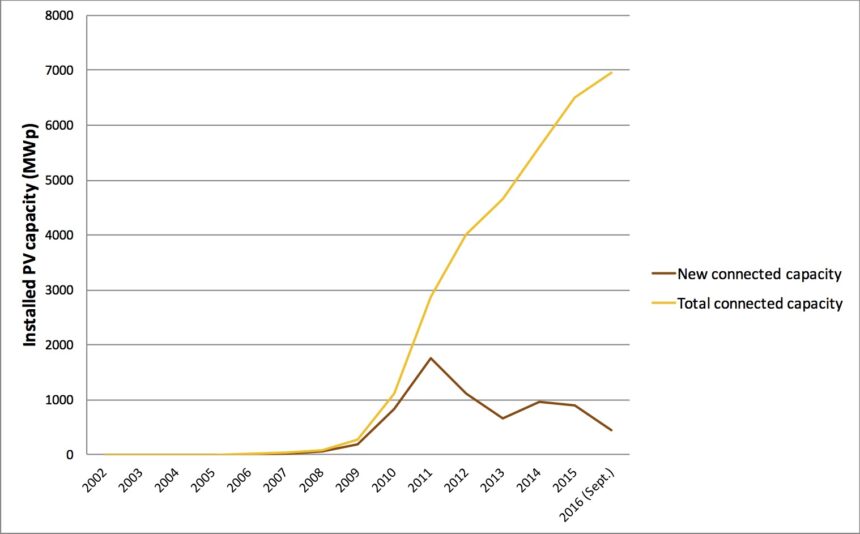

Figure 1: Evolution of grid-connected solar photovoltaics in France: installed capacity in megawatt-peak. (data: SOeS)

However, by 2009 the policy began to have significant impacts as sharp decreases in the costs of photovoltaic equipment combined with a surge in political enthusiasm for renewables. With feed-in tariffs guaranteeing record financial returns, the number of photovoltaic installations rocketed and it became very difficult to evaluate the share of serious projects v. speculative ones. Despite alerts in early 2009, public authorities did not react before January 2010. When they eventually did, the lag between announcement and implementation of tariff cuts only accelerated the rush to register solar projects before cuts were imposed. They also did not have the information channels and the institutional resources to react efficiently. This resulted in high political instability: the policy was reformed again eight months later and no less than twelve regulatory documents about it where published over the year.

The scheme was funded by a levy on electricity use, so this translated in an increase in France’s electricity price for 20 years, the duration of the feed-in contracts. In 2015, feed-in tariffs for photovoltaics represented 35% of the taxes on electricity funding public services, and amounted to € 2,2bn, despite the fact that photovoltaics only accounted for 1% of electricity production in France (Ministry for Ecology, 2016 p. 26).

Unable to contain the policy, the government abruptly froze the scheme in December 2010 – without any warnings. This triggered a violent political crisis which culminated during an extremely tense consultation with stakeholders – though not nearly so tense so as to provoke resignations among the government (this video of a protest before a meeting during the consultation gives an idea of the climate). It ended with a revised version of feed-in tariffs that drastically restricted their ambition and scope to prevent any future crisis, and left the emerging French solar industry decimated. The emerging enthusiasm for photovoltaics plummeted. This is a good example of an ill-managed policy: an instrument was set up in 2006 as a mainly symbolic gesture, with little care for its potential impacts; it turned unexpectedly attractive and the government was unable to monitor its effects and contain its costs. The policy was managed haphazardly for a year, and it ended with an abrupt u-turn that virtually cancelled out the growth of a sector that had just been significantly invested in, when a successful policy should have been able to both contain and sustain growth.

What can we learn from the French & Northern Irish cases?

What do these two stories tell us about renewable energy policies? First, it is not a matter of policy learning: the risk for such instruments to create windfall effects is well identified and the design and use of safeguard mechanisms is documented. These mechanisms may not always work as well as expected, but they were not even tried in both the French and Northern Irish cases. Careless design and limited resources for policy steering can account for the defects of these instruments, and they are likely to stem from unrealistically low expectations.

This suggests that there might be something specific about renewable energy subsidies, an issue that we are exploring as part of a research project on Energy transitions in-the-making. They aim to accelerate and sustain innovation and the widespread deployment of new technology, and ultimately work towards reconfigurations of the energy landscape. They are thus designed to spark novelty and make the unexpected happen (to an extent at least), but should do so in a controlled way. Precisely because of this objective, their calibration is a delicate business, even when conducted carefully. The subtleties of policy design then take on a major role: minor flaws can have major consequences given the potentially exponential effects of incentives.

This is evidenced by one striking common feature of the French and Northern Irish cases: the dramatic political effects triggered by relatively simple and widespread policy instruments. In both cases, the malfunctioning of instruments did not generate bounded, sectoral difficulties; instead, it degenerated into significant political crises that challenged established legitimacies – especially so in Northern Ireland. This is a welcome reminder that market-based instruments are not politics-proof, and that the social and technological dynamics behind their workings cannot be eluded.